I spent twenty years walking Dublin’s streets giving tours. In that time, I had more one-sided conversations with statues than I ever did in my last relationship.

Not on purpose. You just find yourself saying the same things to the same lumps of bronze and stone every day. And they never talk back, which is probably why I kept going.

Start with O’Connell himself. Massive thing at the bottom of the street. Pigeons always sitting on his head, tourists always asking who he was. “Liberator of Ireland,” I’d say. “Big fella with the cloak. No, not the one on the horse, the one pointing.” People never listened properly. I once had a man from Toronto ask if he was Joyce. I said no, but fair guess — both had glasses.

Moving up the street you’ve got Larkin, arms out like he’s stopping traffic. I liked him. Had a bit of presence. Looked like he meant it. Half the groups didn’t know who he was, but I’d stop anyway and say, “Trade unionist, helped people, made speeches.” Then I’d do a pose like him and get a laugh, sometimes. Depends on the crowd.

Phil Lynott’s off Grafton Street. That one gets a reaction. Everyone knows who he is — or pretends to. Took more photos of that statue than I did of my own family. You’d get people lining up to stand beside him, handing me their phones. I don’t think half of them ever listened to Thin Lizzy, but he looks cool and that’s enough.

Molly Malone — nightmare. Always a crowd. People rubbing her chest like it’s going to bring them luck. One woman once asked if she was real. “She’s made of metal,” I said. “I mean, was she a real person,” she said. I said sort of, not really, kind of a song that turned into a myth. She nodded like that made perfect sense and took a selfie anyway.

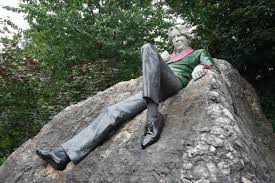

Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square — he’s lying on a rock smirking at you. Bit much. Surrounded by quotes on plinths and sculptures of weird heads. It’s arty. You feel like you should say something clever. I never did. Usually just told people he was brilliant, got arrested for being gay, and wrote The Importance of Being Earnest. That’s more than most guides say.

And then there’s Joyce himself, up near North Earl Street. The one with the stick. Staring off into space like he’s halfway through judging your haircut. People always want a photo with him, even if they don’t know why. I’d tell them he left Dublin and never came back, but wrote about it constantly. “So he liked it?” they’d ask. “Not really,” I’d say. “But it wouldn’t leave him alone.”

Over time you start filling in the gaps. Talking to them when the group’s quiet. “Morning, Jim,” I’d mutter walking past Joyce. “Still here, Molly?” I’d say, stepping over a puddle outside her cart. It sounds mad but when you’ve walked the same route five days a week for a decade, your brain starts inventing company.

They’re reliable, anyway. More than most things in the city. The traffic changes, the shops go bust, the cafés rebrand and double their prices. But the statues stay put. Even when no one’s looking.

You can’t say that about many people.